Thinking in Systems

The title of Donella Meadows’ masterpiece Thinking in Systems explains precisely what the book will do in 254 concise pages that are a joy to read: it will very likely—and very likely permanently—change the way you think about the world around you.

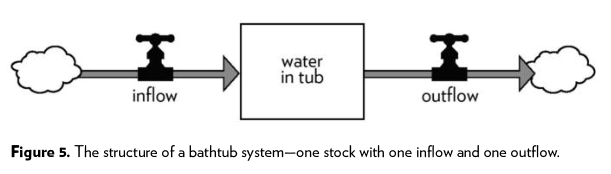

Key concepts like stocks, flows, and feedback loops are introduced using simple models and metaphors like a bathtub filling and draining, or a home’s temperature adjusted via thermostat:

The tub can’t fill up immediately, even with the inflow faucet on full blast. A stock takes time to change, because flows take time to flow. That’s a vital point, a key to understanding why systems behave as they do. Stocks usually change slowly. They can act as delays, lags, buffers, ballast, and sources of momentum in a system. Stocks, especially large ones, respond to change, even sudden change, only by gradual filling or emptying.

(And speaking of bathtubs, if you’ve ever had to adjust the temperature in a shower with a knob unusually far away from the faucet, you’ve experienced the challenges of dealing with a delayed feedback loop.)

Quickly, yet almost imperceptibly, Meadows builds on these simple models and begins describing much more complex systems, including the kinds present all around us:  After the first chapter introducing these core concepts, you will already start seeing them all around you, and soon find yourself thinking about the relationship between stocks and flows in your home, your work, your city, and the economy.

After the first chapter introducing these core concepts, you will already start seeing them all around you, and soon find yourself thinking about the relationship between stocks and flows in your home, your work, your city, and the economy.

Within that first chapter, Meadows also lays out the reason she believes systems thinking is so important to understanding our world, which also clarifies the relevance for any leader:

Once we see the relationship between structure and behavior, we can begin to understand how systems work, what makes them produce poor results, and how to shift them into better behavior patterns. As our world continues to change rapidly and become more complex, systems thinking will help us manage, adapt, and see the wide range of choices we have before us. It is a way of thinking that gives us the freedom to identify root causes of problems and see new opportunities.

The models given are all just examples of the underlying category of dynamic system, which Meadows defines like this:

So, what is a system? A system is a set of things-people, cells, molecules, or whatever-interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time. The system may be buffeted, constricted, triggered, or driven by outside forces. But the system’s response to these forces is characteristic of itself, and that response is seldom simple in the real world.

While at first it seems absurd to assert that everything is a system, Meadows will steadily bring you to exactly that conclusion:

A school is a system. So is a city, and a factory, and a corporation, and a national economy. An animal is a system. A tree is a system, and a forest is a larger system that encompasses subsystems of trees and animals. The earth is a system. So is the solar system; so is a galaxy. Systems can be embedded in systems, which are embedded in yet other systems.

An important point here is not that suddenly she (or anyone else for that matter) has created systems thinking; rather it’s a way of understanding and analyzing phenomena that have always existed. This is not the creation of a new form of knowledge, but rather a journey of discovery and description of something fundamental we already intuitively understand about our world:

Every person we encounter, every organization, every animal, garden, tree, and forest is a complex system. We have built up intuitively, without analysis, often without words, a practical understanding of how these systems work, and how to work with them. Modern systems theory, bound up with computers and equations, hides the fact that it traffics in truths known at some level by everyone. It is often possible, therefore, to make a direct translation from systems jargon to traditional wisdom.

Besides stocks, flows, and feedback loops, there are three more key concepts that Meadows introduces early on that recur throughout the book (and which you’ll also begin noticing all around you):

A system’ is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something. If you look at that definition closely for a minute, you can see that a system must consist of three kinds of things: elements, interconnections, and a function or purpose.

Soon after, Meadows touches on something about those three key components of a system — elements, interconnections, and purpose—that matters a great deal in the context of an organization, which is that when problems occur, people tend to first blame the elements of the system (often other people), ignoring the other two:

Changing elements usually has the least effect on the system. If you change all the players on a football team, it is still recognizably a football team. (It may play much better or much worse-particular elements in a system can indeed be important.) A tree changes its cells constantly, its leaves every year or so, but it is still essentially the same tree. Your body replaces most of its cells every few weeks, but it goes on being your body. A system generally goes on being itself, changing only slowly if at all, even with complete substitutions of its elements-as long as its interconnections and purposes remain intact. If the interconnections change, the system may be greatly altered. It may even become unrecognizable, even though the same players are on the team. Change the rules from those of football to those of basketball, and you’ve got, as they say, a whole new ball game. If you change the interconnections in the tree-say that instead of taking in carbon dioxide and emitting oxygen, it does the reverse-it would no longer be a tree.

That perspective helps explain why so many “re-orgs” don’t seem to actually produce much more than new org charts, and should give pause to a new leader eager to make changes and looking first at people, departments, or product lines:

Putting different hands on the faucets may change the rate at which the faucets turn, but if they’re the same old faucets, plumbed into the same old system, turned according to the same old information and goals and rules, the system behavior isn’t going to change much.

Another critical theme of the book is the importance of correctly understanding what goal a system is trying to achieve, particularly in the special case where a person (or people) are responsible for determining those goals:

Systems, like the three wishes in the traditional fairy tale, have a terrible tendency to produce exactly and only what you ask them to produce. Be careful what you ask them to produce. If the desired system state is good education, measuring that goal by the amount of money spent per student will ensure money spent per student. If the quality of education is measured by performance on standardized tests, the system will produce performance on standardized tests. Whether either of these measures is correlated with good education is at least worth thinking about. These examples confuse effort with result, one of the most common mistakes in designing systems around the wrong goal.

This also reinforces the importance of care when designing incentives within an organization, as well as recognizing when there are hidden incentives at work driving behavior (eg, where honesty is formally requested, yet sycophancy is informally rewarded, bad news flows quite slowly up the chain of command).

While in some cases there is nominally someone “in charge” of a system, many of the most important ones all around us (including industries and economies) are essentially self-organizing—yet there is always a goal at work. Meadows points out how important the flow of information (part of the interconnections that communicate and reinforce — or even redefine—the system’s goal) can be to the overall system health:

Missing information flows is one of the most common causes of system malfunction. Adding or restoring information can be a powerful intervention, usually much easier and cheaper than rebuilding physical infrastructure. The tragedy of the commons that is crashing the world’s commercial fisheries occurs because there is little feedback from the state of the fish population to the decision to invest in fishing vessels. Contrary to economic opinion, the price of fish doesn’t provide that feedback. As the fish get more scarce they become more expensive, and it becomes all the more profitable to go out and catch the last few. That’s a perverse feedback, a reinforcing loop that leads to collapse. It is not price information but population information that is needed.

In the context of book publishing, one of the industries I know best, I suspect many who work in it would state that system’s goal as either an economic argument like “maximize book sales,” or a cultural one like “maximize the amount of reading”. Yet the data shows Americans in particular are reading fewer books while publishers see fewer dollars earned with each book published. I’d argue that for better or worse, the actual goal of the current system is to maximize the number of books published, something it appears to be doing swimmingly.

A recurring theme in the books chosen for this blog is the importance for leaders to become comfortable with discomfort and ambiguity, both of which become only more common with increased responsibilities. Meadows’ descriptions and explanations of systems will help you think about the systems you’re a part of, but that doesn’t mean you should expect easy answers or quick fixes:

Self-organizing, nonlinear, feedback systems are inherently unpredictable. They are not controllable. They are understandable only in the most general way. The goal of foreseeing the future exactly and preparing for it perfectly is unrealizable. The idea of making a complex system do just what you want it to do can be achieved only temporarily, at best. We can never fully understand our world, not in the way our reductionist science has led us to expect. Our science itself, from quantum theory to the mathematics of chaos, leads us into irreducible uncertainty. For any objective other than the most trivial, we can’t optimize; we don’t even know what to optimize. We can’t keep track of everything. We can’t find a proper, sustainable relationship to nature, each other, or the institutions we create, if we try to do it from the role of omniscient conqueror.

While that may sound fatalistic (or at least pessimistic), I think it’s intended to be simply realistic, and another theme running through many of the books chosen here is the need to first and foremost see and accept reality for what it is, even if you desperately want to change it.

There is actually a warm optimism underneath all the realism, including a reminder that numbers and spreadsheets are incapable of modeling or measuring what ultimately matters most:

Don’t be stopped by the “if you can’t define it and measure it, I don’t have to pay attention to it” ploy. No one can define or measure justice, democracy, security, freedom, truth, or love. No one can define or measure any value. But if no one speaks up for them, if systems aren’t designed to produce them, if we don’t speak about them and point toward their presence or absence, they will cease to exist. Aim to enhance total systems properties, such as growth, stability, diversity, resilience, and sustainability-whether they are easily measured or not.

Near the end of the book, Meadows offers some advice for the budding Systems thinker, and it’s advice that’s suited to the beginning of any (or every) undertaking:

What’s appropriate when you’re learning is small steps, constant monitoring, and a willingness to change course as you find out more about where it’s leading.

Thinking in Systems is available in multiple formats from Bookshop.org.