Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

One of the signals I use in deciding whether a book is worth reading is whether it is somehow connected to the people and organizations I already know and respect. Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, by Carlota Perez, is one of my favorite examples.

I first heard of the book from a reference on Simon Wardley’s blog. Simon is one of my favorite writers on strategy (and he’s a blast to watch in action giving a conference talk). Then, when I looked the book up, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that it’s published by Edward Elgar Publishing, which was actually a customer of Safari Books Online (now the O’Reilly learning platform), my employer at the time. And finally, when the book arrived in the mail, I was positively delighted to see that one of the testimonials on the back cover was from Bill Janeway, one of the sharpest minds around at the intersection of economics, technology, and venture capital (and also a board member at O’Reilly Media, Safari’s then-parent-company).

So it’s fair to say I started reading with high expectations — and Perez quickly exceeded them. After finishing this book, you will have a new framework through which to understand and analyze not just technology changes, but how they fit into the wider social, political, and economic landscape.

She starts the book with a scene from the birth of the computer age:

On a day like any other in November 1971, a small event in Santa Clara California was about to change the history of the world. Bob Noyce and Gordon Moore launched Intel’s first microprocessor, the precursor of the computer on a chip. It was the big-bang of a new universe, that of all-pervasive computing and digital telecommunications. Chips were powerful, they were cheap and they opened innumerable technological and business possibilities.

After enumerating all of the concomitant changes in the financial landscape (eg, the rise of venture capital, an explosion in “derivatives”, and the transformation of vast swaths of the middle class into day traders), she then directly compares those events starting in 1971 with a previous technology-driven boom (and bust) — one that began with the launch of Henry Ford’s Model T in 1908:

By the mid-1920s, the New York Stock Market was perceived as the engine moving the American economy and even the world’s. As was to happen later, in the 1980s and 1990s, financial geniuses appeared by the dozens and investment in stocks or real estate seemed almost guaranteed to grow and grow in an unending bull market. Great wealth for the players was the result; irrational exuberance was the mood. By the end of the 1920s even widows, small farmers and shoe-shine boys were putting their money into that glorified casino. The crash was unexpected; the following recession and depression were exceptionally deep and prolonged.

And then she sets up the rest of the book by laying out her main thesis: that the similarities between the events of the early and late 1900s are not a special case, rather just the latest variations of a cycle of “surges” (similar to Schumpeter’s waves of “creative destruction”) that lends credence to the proverbial saying (often mis-attributed to Mark Twain), “history never repeats itself, but it rhymes”:

This sequence had happened three times before in a similar — though each time specific — manner. A decade after the first industrial revolution opened the world of mechanization in England and led to the rapid extension of the network of roads, bridges, ports and canals to support a growing flow of trade, there was canal mania and, later, canal panic. About 15 years after the Liverpool-Manchester rail line inaugurated the Age of Steam and Railroads, there was an amazing investment boom in the stock of companies constructing railways, a veritable ‘railway mania’ which ended in panic and collapse in 1847. After Andrew Carnegie’s Bessemer steel mill in 1875 gave the big-bang for the Age of Steel and heavy engineering, a huge transformation began to change the economy of the whole world, with transcontinental trade and travel, by rail and steamship, accompanied by international telegraph and electricity. The growth of the stock markets in the 1880s and 1890s was now, not only in railways but also in industry, not mainly national but more and more truly international. The crashes happened, in different forms, in the USA and Argentina, in Italy and France and in many other parts of the world.

To be fair, Perez’s case was not a tough sell for me: As an undergraduate studying Communications at the same time that the Web was coming of age — I arrived on campus at the University of Illinois in Champaign, Illinois in 1995 where I was handed my first-ever email address— I remember readings about the history of the telegraph and being struck by how it much it sounded like what was being said—and feared—about the Internet.

But what really hooked me in was how Perez takes care to place the technology piece squarely within a surrounding social, economic, and political context:

Each time around, what can be considered a ‘new economy’ takes root where the old economy had been faltering. But it is all achieved in a violent, wasteful and painful manner. The new wealth that accumulates at one end is often more than counterbalanced by the poverty that spreads at the other end. This is in fact the period when capitalism shows its ugliest and most callous face. It is the time depicted by Charles Dickens and Upton Sinclair, by Friedrich Engels and Thorstein Veblen; the time when the rich get richer with arrogance and the poor get poorer through no fault of their own; when part of the population celebrates prosperity and the other portion (generally much larger) experiences outright deterioration and decline.

Later in the book Perez describes the circumstances by which large portions of the population become convinced that “this time things are different”:

In spite of the recurring ups and downs in the economic and social performance of capitalism, there seems to be an underlying faith in the eventual arrival of a period without cycles and without social problems as a result of the operation of the system. This mixture of ideas and convictions with yeamings and desires resurfaces with great strength during two particular phases of the surge: Frenzy and Synergy. In the first, it is the growth of the financial bubble and the incredible profits achieved that create the delusion of a new economy, which is all the more credible the more money arrives at the believer’s bank. In the second, it is the steady growth and the gradual diffusion of well-being for a relatively long period that create the illusion of an ever-improving society. The first mirage will be broken by the bursting of the bubble; the second by the growing social discontent followed by the economic decline of the established production structure.

In a news and information landscape dominated by the immediate and instantaneous, Perez gives us good reason to take a longer perspective, much longer even than the typical “5-year plan” at the heart of many corporate budgets:

This book holds that the sequence: technological revolution-financial bubble-collapse-golden age-political unrest, recurs about every half century and is based on causal mechanisms that are in the nature of capitalism.

One of key features of the system Perez describes is “the much greater inertia and resistance to change of the socio-institutional framework in comparison with the techno-economic sphere, which is spurred by competitive pressures,” something we see playing out right now with battles between Uber and taxi drivers, AirBnB and city tax collectors, and drone operators and the FAA. (On the other hand, I can remember during one of my first visits to Las Vegas the strict prohibition against cameras or mobile phones anywhere near the games — now of course it would look strange to not see winners taking selfies.)

In Chapter 2, Perez goes deeper into defining what she means by a technological revolution:

A technological revolution can be defined as a powerful and highly visible cluster of new and dynamic technologies, products, and industries, capable of bringing about an upheaval in the whole fabric of the economy and of propelling a long-term upsurge of development. It is a strongly interrelated constellation of technical innovations, generally including an important all-pervasive low-cost input, often a source of energy, sometimes a crucial material, plus significant new products and processes and a new infrastructure. The latter usually changes the frontier in speed and reliability of transportation and communications, while drastically reducing their cost.

But she points out that the reason they’re so significant is that they do not remain confined to the industry in which they were born, ultimately reshaping entire economies and social structures:

The irruption of such significant clusters of innovative industries in a short period of time would certainly be enough reason to label them as ‘technological revolutions.’ Yet what warrants the title for the present purposes is that each of those sets of technological breakthroughs spreads far beyond the con- fines of the industries and sectors where they originally developed. Each provides a set of interrelated generic technologies and organizational principles that allows and fosters a quantum jump in potential productivity for practically all economic activities. This leads each time to the modernization and regeneration of the whole productive system, so that the general level of efficiency rises to a new height every 50 years or so.

We’re all familiar with how quickly technology itself can spread, but again it’s the impact on and interplay with the financial, political, and social institutions that governs the pace of the wider changes, and those happen with a predictable (if not identical) pattern.

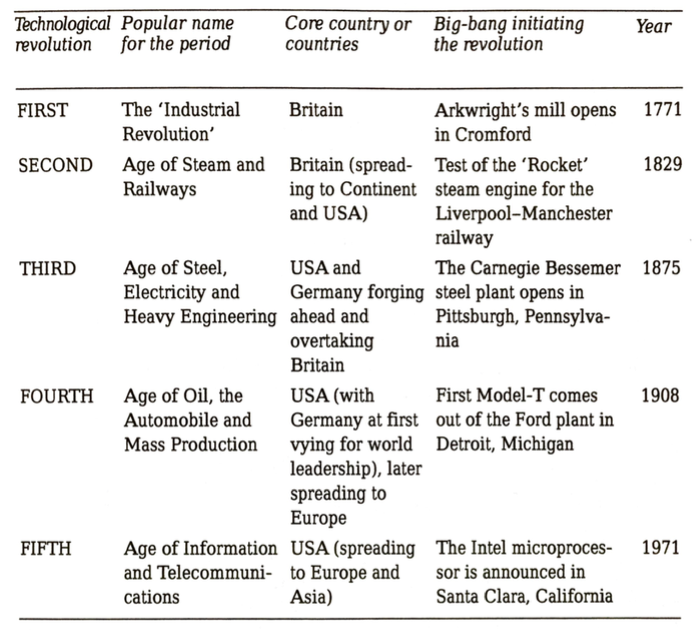

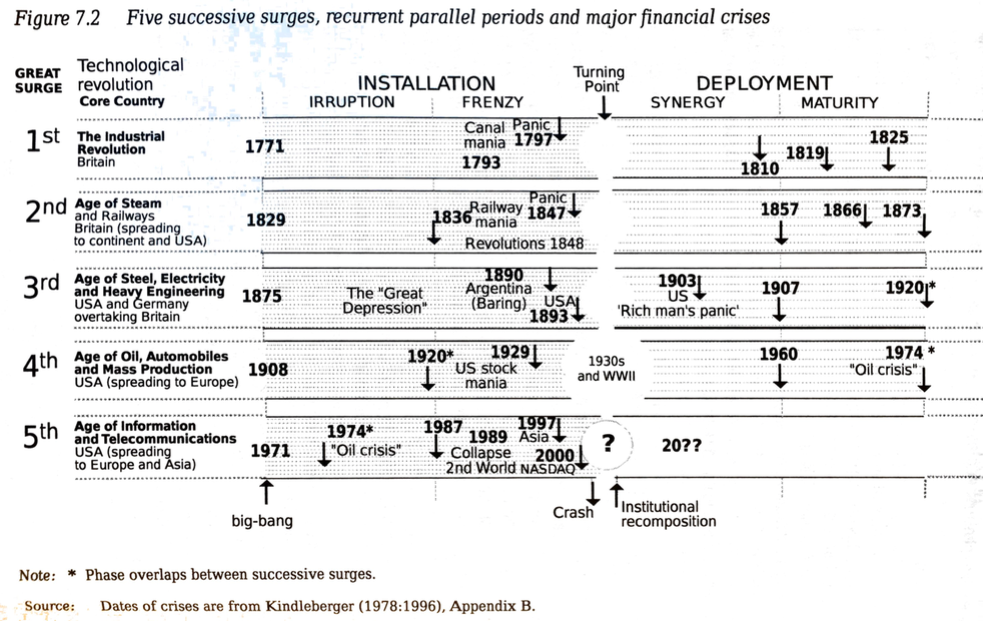

Perez then goes on to identify the five technological revolutions covered in the book, beginning with the Industrial Revolution, starting in 1771 in Britain on through the Age of Information and Telecommunications, kicking off 200 years later in the US:

Perez defines a singular “big-bang” event signaling the beginning of each, but with no similar indication of the “end”; her explanation for why helps explain a key part of the premise of the book:

By contrast, any attempt at indicating an ending date for each revolution would be relatively meaningless. It is true that certain events can be felt by society as announcing the ‘end of an era’, such as the 1973 oil crisis and the 1971 breakdown of the Bretton Woods agreement on the dollar. Nevertheless, as will be discussed in the next chapter, each set of technologies undergoes a difficult and prolonged period of stretching when the impending exhaustion of its potential becomes increasingly visible. This phenomenon is crucial to the present interpretation. When each technological revolution irrupts, the logic and the effects of its predecessor are still fully dominant and exert powerful resistance. The generalized shift into ’the logic of the new’ requires two or three turbulent decades of transition from one to the other, when the successful installation of the new superior capacities accentuates the decline of the old. By the time the process has fully taken place, the end of the previous revolution is little more than a whimper. (Emphasis added.)

My own take on why it takes a few decades for the “logic of the new” to proliferate would include something Perez doesn’t spend much time discussing, which is simply that those in power age out of those positions of power. It’s less about large populations changing their mental models of the world, and more about a new generation of workers and leaders replacing those now-outdated models with their own.

Chapter 2 includes two critical lesson about the creation and diffusion of technological innovation: first, that the innovations frequently come out of the very industries or sectors they disrupt; second, that no technology is an “overnight success” and usually takes much, much longer to germinate than we realize:

The technologies and products involved are not only those where the major breakthroughs have occurred It is often the interlinking of some of the new and some of the old that generates the revolutionary potential. In fact, many of the products and industries coming together into the new constellation had already existed for some time, rather in a relatively minor economic role or as important complements for the prevailing industries. This was the case of coal and iron, which after a long history of usage during and before the Industrial Revolution, were transformed by the steam engine into the motive industries of the Age of Railways. Oil was developed for many uses since the 1880s by an extremely active industry; the same can be said about the internal combustion engine and for the automobile, which was produced as a luxury vehicle for quite some time. But it is the conjunction of all three with mass production that makes them become part of a veritable revolution. Electronics existed since the early 1900s and in some ways was crucial in the 1920s; transistors, semiconductors, computers and controls were already important technologies in the 1960s and even earlier. Yet it is only in 1971, with the microprocessor, that the vast new potential of cheap microelectronics is made visible; the notion of ‘a computer on a chip’ flares the imagination and all the related technologies of the information revolution come together into a powerful cluster.

(Keep those time frames in mind the next time you read about Solar energy being “around for 50 years and not taking off”, or references to the “AI Winter” of the 1970s and 1980s.)

Perez makes another key point about the relationship between each successive revolution, which is that the new infrastructure resulting from one revolution is often a key ingredient in the subsequent:

The iron railways of the second technological revolution led to national networks of rail transport and telegraph The steel railways of the third revolution created transcontinental networks that together with the steel steamships and worldwide telegraph, facilitated the functioning of truly international markets. Regarding electricity, the setting up of the basic electrical networks made the electrical equipment industry into one of the main engines of growth of the third technological revolution; whereas, during the fourth, it was its role as a ’utility’, as a universal stance encompassing every firm and every home, that made it a crucial infrastructure for the diffusion of the mass-production revolution.

Given that we’re nearing the 50-year mark on the Age of Information and Telecommunications, one might conclude that the infrastructure of the Internet, the World Wide Web, pervasive mobile broadband, and the “internet of things” including mobile computers, phones, and sensors on nearly every person and in many building and vehicles, may be part of the core “infrastructure” for whatever revolution comes next.

Perez also talks more about how the “new way” of doing things introduced by each technological revolution becomes just “common sense” and fades into accepted and established ways of doing things:

The task becomes harder the further one goes into the past because in real life the paradigm is mostly an imitative model made up of implicit principles that soon become unconscious ‘talent’ and later get subsumed into ‘rules of thumb’.

Further on, Perez dig much deeper into the role of social and political forces in shaping the technological revolution, underscoring how much of it is an interplay rather than a linear cause-and-effect:

Societies are profoundly shaken and shaped by each technological revolution and, in turn, the technological potential is shaped and steered as a result of intense social, political and ideological confrontations and compromises.

And it’s easy to recognize today’s tensions around AI and automation (especially in manufacturing and commercial driving — long two of the biggest sectors for quality blue-collar jobs) in Perez’s description of the forces at work in society’s response to technology changes:

It is precisely the need for reforms and the inevitable social resistance to them that lies behind the deeper crises and longer-term cyclical behavior of the system. Each technological revolution, originally received as a bright new set of opportunities, is soon recognized as a threat to the established way of doing things in firms, institutions, and society at large.

Much is made of the adoption curves of, say, smartphones compared with VCRs (at one point the fastest-adopted consumer technology in history), or even with traditional landline telephones, which took decades to reach the same percentage of the population that bought smartphones within months. Typically the analysis involves some degree of breathless wonder at this new rate of change, but what’s missed is just how strange the telephone was upon its introduction, and relatively limited in its utility. By contrast, for all of Steve Jobs’ brilliance, Apple launched the iPhone to a market that had been talking on telephones (and watching screens) all of their lives, and which already spent much of their working days using computers of some sort. The iPhone was a brilliant combination of capabilities elegantly packaged, but I’d say it’s more consistent with what is seen during the later stages of a particular technological revolution as Perez describes it:

when an innovation is within the natural trajectory of the prevailing paradigm, then everybody — from engineers through investors to consumers - understands what the product is good for and can probably suggest what to improve. Even such minor and doubtfully useful products as the electric can-opener or the electric carving knife are thought worth designing, producing, buying and using in a world that is already accustomed to dozens of electrical appliances in the kitchen. The same happens with the successive applications of the general principles of the prevailing paradigm. In the case of continuous mass production, for example, after manufacturing had fully developed all its principles and refined its organizational practices, the task of applying the model to any other activity became straightforward. Mass tourism, of the ‘assembly-line’ type, moving people from airplane to bus, from bus to hotel and from hotel to bus, was obvious to conceive, easy to put into practice and readily accepted by consumers at the time.

Taking that view — that we are in the late stages of the Information & Telecommunications revolution, when everyone is already accustomed to hundreds of apps on their smartphone screen—the acceleration seen when comparing growth of, say, Facebook vs. Instagram vs. Snapchat, makes more sense. Snapchat deserves much credit for their execution, but their growth rate was only made possible by a market already fully saturated with smartphones and users accustomed to using them incessantly (neither of which was the case at Facebook’s birth). As Perez puts it later on:

The accumulated experience and the already well-developed infrastructure and business practices create very favorable conditions for the fast diffusion of the last products and industries exploiting the established externalities. They are also routinized enough to make it relatively easy to begin spreading out geographically, reaching for peripheral markets or for lower-cost production.

Yet there is a limit—and perhaps in hindsight we may consider Pokémon Go the defining instance of reaching it—and when new products can saturate the market nearly instantaneously, it’s probably a good sign the next revolution is on the horizon:

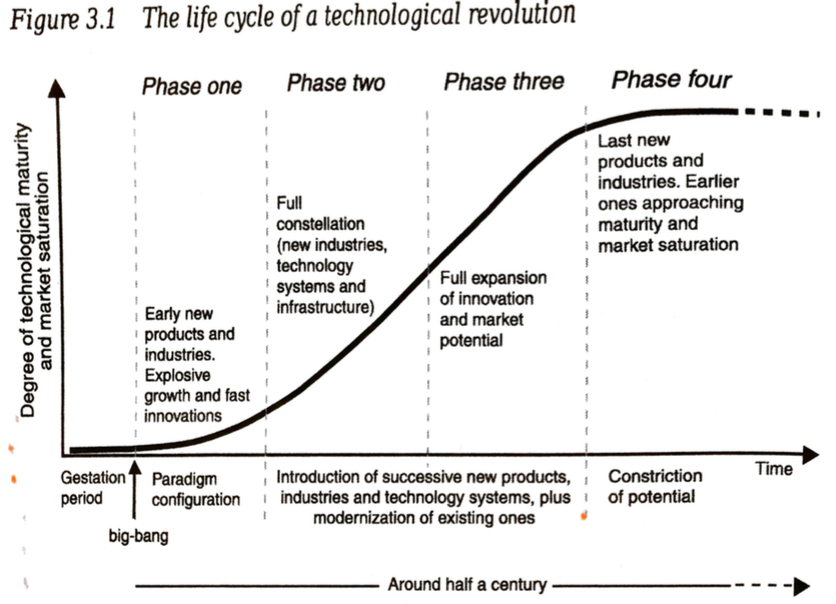

Yet, trajectories are not eternal. The potential of a paradigm, no matter how powerful, will eventually be exhausted. Technological revolutions and paradigms have a life cycle of about half a century, which more or less follows the type of logistic curve characteristic of any innovation.

And lest we think the pace of obsolescence we’ve come to accept from our phones is something new, Perez includes an excerpt from David A. Wells, writing about the end of the 19th century:

The numerous and expansive steamer constructions of 1870-73, being unable to compete with the constructions of the next two years, were nearly all displaced in 1875-76, and sold for half, or less than half, of their original cost. And within another decade these same improved steamers of 1875-76 have, in turn, been discarded and sold at small prices, as unfit for the service of lines having an established trade, and replaced with vessels fitted with triple-expansion engines and saving nearly fifty per cent in the consumption of fuel. And now ‘quadruple-expansion’ engines are beginning to be introduced and their tendency to supplant the ‘triple expansion’ is unmistakable.

Graphically, the phases Perez describes are shown below, taking on a familiar “S-curve” shape:

While we can lament the banality of a seemingly endless stream of “me-too” apps, games, and “SaaS solutions”, the good news is that this point in the cycle is seeding the conditions for the next technological revolution, likely built in large part on the infrastructure of the current one, and often by combining or adapting technologies that already exist in new ways previously impossible absent that infrastructure:

Crude versions of the high pressure engine were tried in the early 1800s to increase the productivity of textile machinery; ’scientific management’ of work organization, which is the core of mass production, was first developed by Taylor at the turn of the century to increase the productivity of moving steel products in the steel yards; automation was given trial runs by the automobile industry in the early 1960s, control instruments in their pre-digital forms went far in development in the process industries from early on, numerical control machine tools were introduced in shoe manufacturing and aerospace in the 1960s and 1970s. So, the introduction of some truly new technologies can be tied to revitalizing mature industries in trouble.

But Perez points out that it’s the crucial role of financial capital that will really drive the next revolution:

As the low-risk investment opportunities in the established paradigm begin to diminish, either in innovation or in market expansion, there is a growing mass of idle capital looking for profitable uses and willing to venture in new directions. Thus, the exhaustion of a paradigm brings with it both the need for radical entrepreneurship and the idle capital to take the high risks of trial and error.

Under these conditions several strands of innovation come together, some from the big firms overcoming obstacles, others from novel entrepreneurs with new ideas and others associated with the many underutilized or marginalized innovations that had been introduced before.

Later in Part 1, Perez goes into more detail about the key stages of each revolution, as well as the interplay between revolutions, especially the repeated cycle of tensions created during the initial clash between old and new:

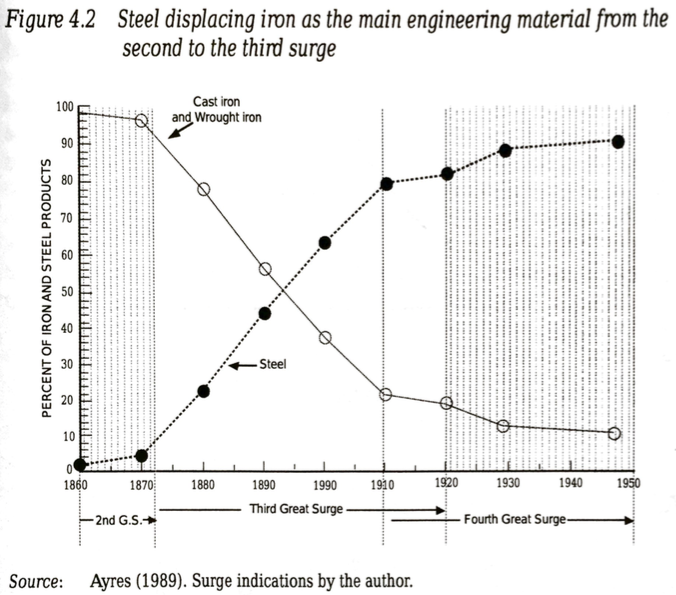

Schumpeter’s notion of ’creative destruction’ aptly portrays the effects of radical innovations. When the core products of a technological revolution start coming together, they inevitably clash with the established environment and the ingrained ways of doing things. Arkwright’s water frame was a clear threat to hand spinners both in England and in India. The Liverpool-Manchester railway announced the demise of the horse-drawn carriage for long-distance passenger travel, affecting various occupations from innkeepers to veterinarians. The Suez Canal practically eliminated sailing ships from the route to India, while, by cutting travel time from three months to one, it made obsolete the network of huge cargo depots in England, threatening the power of the big trading companies and opening opportunities for smaller ones. Cheap Bessemer steel was a clear menace to wrought iron producers (see Figure 4.2). The fast, powerful steel steamships with refrigerated cargo opened the world meat and produce markets of the North to competition from the countries of the southern hemisphere. The mass-produced automobile was a clear foreboding of the displacement of steam-powered trains and horse-drawn carriages as the main means of passenger travel.

I found Perez’s framing of “two moneys” later on tremendously helpful in understanding some of the tensions inherent in the transition from one wave to the next:

The stress also comes, among other things, from the much greater productivity of the industries and activities associated with the technological revolution in relation to traditional ones. This difference produces such rapid and constant changes in their relative values that, as discussed in Chapter 6, there is a coexistence of ‘two moneys’, one for the new economy and another for the old, rather than the assumed single and universal measure of ’standard units’ of value. If you could in the 1960s buy five cars for the price of one computer and in the 1990s twenty computers for the price of one car, it is difficult to gauge the relative worth of goods. This general uncertainty makes the inflation in stock values all the more credible. (Emphasis added)

And her list of the kinds of tensions created during a transition reminds me of those commercials for crime dramas “ripped from the headlines” and might as well describe current analysis of Brexit and the rise of nationalism and populism around the world:

Thus, the irruption of the technological revolution also signals a cleavage in the fabric of the economy along several lines of tension:

- between the new industries and the mature ones;

- between the modern firms —whether new or upgraded by the new methods - and the firms that stay attached to the old ways;

- regionally, between the strongholds of the now old industries and the new spaces occupied or favored by the new industries;

- in capabilities, between those that are trained to participate in the new technologies and those whose skills become increasingly obsolete;

- in the working population, between those that work in the modern firms or live in the dynamic regions and those that remain in the stagnant ones and are threatened with unemployment or uncertain incomes;

- structurally, between the thriving new industries and the old regulatory system, and

- internationally, between the fortunes of those countries that ride the wave of the new technologies and those that are left behind.

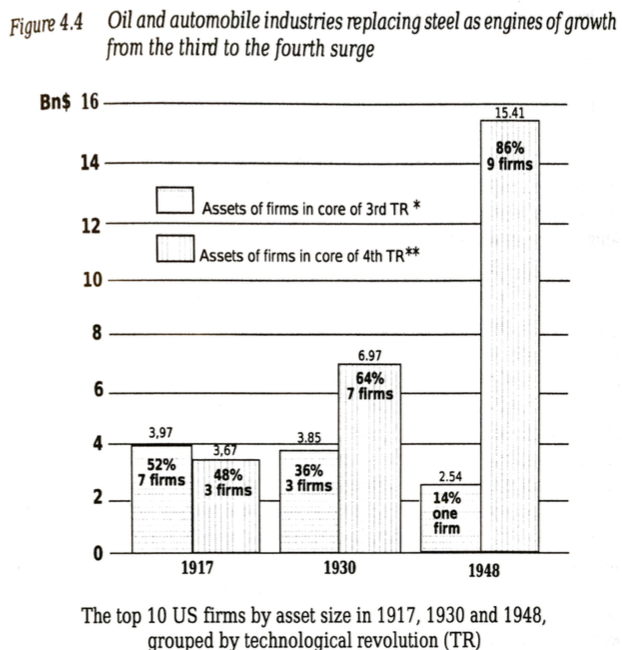

Chapter 4 includes two of what I think are the book’s most important charts, both related to understanding what happens during successive revolutions. While both describe changes early in the 20th century, both have implications for what’s in progress right now early in the 21st.

The first compares the relative market share of iron vs. steel for engineering applications. It’s notable how complete the overtaking was, but you can also see how gradual it must have felt to those living through it — the curve looks quite steep in a chart, but the transition took decades (like the apocryphal simmering frog):

And the other key chart in chapter 4 is also relevant as much for how it applies to today as for its usefulness in understanding the past:

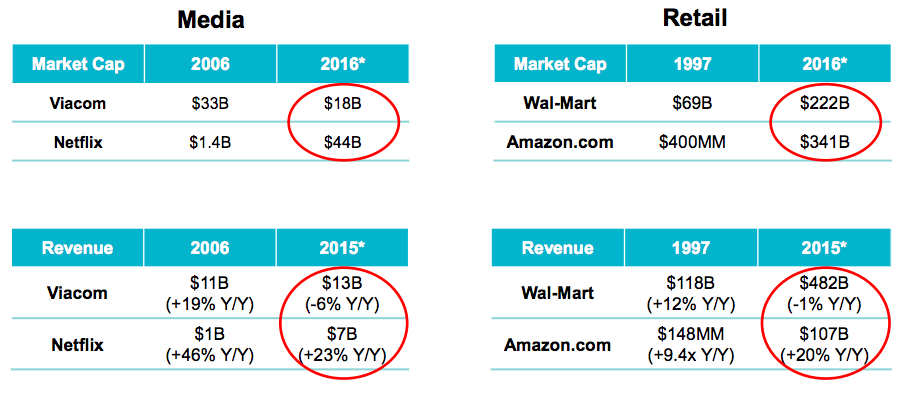

The chart (covering a time period a bit later than the one above) shows how Oil, Auto, and Appliances firms replaced Steel (and Meatpacking!) among the ranks of the largest US firms. Now consider a similar look atop the S&P 500 today, where the takeover by companies of the 5th surge is well underway:

[Top 10 S&P 500 companies as of this writing showing dominance of tech (5th wave) companies](/img/s-p-leaders.png)

And here’s another example of that sort of overtaking, pulled from Mary Meeker’s most recent Internet Trends presentation:

Perez divides each revolution into two halves, Installation and Deployment, and further splits each of those (with Irruption and Frenzy making up the Installation period, and Synergy and Maturity composing the Deployment period). A core of her theory is that the last period of one revolution (Deployment) overlaps with the first period of the next (Irruption). Her description of both of those periods read through a modern context is instructive. Here she is on the strain typically felt during the tail end of the Deployment period, which sounds eerily familiar today:

The acts of machine breaking (Luddism) of the 1810s or the protests against the Corn Laws and demands for universal suffrage that led to the ’Peterloo’ massacre in Britain in 1819 are widely separated historically and ideologically from the violent protests of May 1968 in the main countries of continental Europe. However, the dissatisfaction and frustration driving them both is of a fundamentally similar origin: capitalism had been making too many promises about social progress and not delivering enough, showing too much capacity for wealth creation and not distributing enough.

And again since there’s an overlap with the Irruption of the next stage, we’d expect to see some features of that playing out right now as well:

Despair and impotence affect those losing out, be they workers who lost their jobs, industries with declining profits and markets or decision-makers in government whose policies no longer work. For those wedded to the old model and especially to the ideas and ideals of the established paradigm these are times of bewilderment. The world seems to be falling apart and the old behaviors and policies are impotent to save it. Meanwhile, the new entrepreneurs are gradually articulating the new ideas and successful behaviors into a new best- practice frontier that serves as the guiding model or techno-economic paradigm.

Divergence between the new and the old characterizes this phase. Inside political parties, both left and right, a cleavage takes place between the modernizers and the nostalgic, sometimes leading to divisions, recompositions or completely new movements. There is also a marked revival of the stock market, first in relation to the new industries and soon with new instruments and various forms of speculation. (Emphasis added as the Dow Jones sets new records…)

Perez also notes that these various stages tend to propagate at different rates throughout the world (though arguably less so as world economies increase their connectedness), which helps explain why it is hard to identify and track these sequences from standard economic and financial data (as compared with her admittedly simplistic narrative descriptions of each):

This will help understand why such recurrent sequences are not easy to identify in the economic data series. In fact if things were really as simple and straightforward as the previous narrative could be seen to imply, the process would be obvious to everyone and the debate about long waves, of one form or another, would have been solved in favor of them long ago.

In addition to variations in how these things spread geographically, they of course affect different parts of the economy at different rates, and the inherent nature of the disruption caused by the waves of technology revolution can frustrate attempts to measure them using standard economic methods (the “two-money” problem again):

A further complication arises from the fact that most of the measuring attempts use money values (sometimes with constructed ’constant’ values). This is not valid for a simple reason: the quantum jump in productivity brought about by a technological revolution leads during the period of installation to the coexistence of ’two moneys’ operating under the guise of one. The change in the relative price structure is radical and centrifugal. Money buying electronics and telecommunications today does not have the same value as money buying furniture or automobiles, and the difference has been growing since the early 1970s The price of steel, in the installation period of the third surge, came down because of immense increases in productivity, while that of iron was forced down by competition in the market.

(I’d argue that you can see glimmers today of the same dynamic described in the last sentence when comparing the cost/performance trajectory of solar energy vs. the price of oil.)

While the first part of the book focuses on the technological revolutions, the the second part of the book shifts to the other eponymous half, financial capital. She opens by establishing a distinction between two fundamental types of capital: production capital and financial capital:

Financial capital is mobile by nature while production capital is basically tied to concrete products, both by installed equipment with specific operational capabilities and by linkages in networks of suppliers, customers or distributors in particular geographic locations. Financial capital can successfully invest in a firm’ or a project without much knowledge of what it does or how it does it. Its main question is potential profitability (sometimes even just the perception others may have about it). For production capital, knowledge about product, process and markets is the very foundation of potential success. The knowledge can be scientific and technical expertise or managerial experience, it can be innovative talent or entrepreneurial drive, but it will always be about specific areas and only partly mobile. Both financial capital and production capital face risks that vary with circumstances from great to minimal. Yet, while financial capital can choose widely how to invest its money, avoiding or withdrawing from risks which it deems too high for the likely returns, most agents of production capital are in path-dependent situations and must find alternative actions within a limited range, often needing to lure financial capital or face failure.

The key takeaway for me on the distinction was the fluid (and often fickle) nature of financial capital —and that very nature is part of what makes it so critical to understanding the underlying cycles at the heart of the book:

Financial capital is footloose by nature; production capital has roots in an area of competence and even in a geographic region. Financial capital will flee danger; production capital has to face every storm by holding fast, ducking down or innovating its way forward or sideways. Yet, though the notion of progress and innovation is associated with production capital —and rightly so— ironically when it comes to radical change, incumbent production capital can become conservative and then it is the role of financial capital (whether from family, banks or ‘angels’) to enable the rise of the new entrepreneurs.

One of the most tantalizing charts in the book (again, written in 2002) is the one overlaying historic financial downturns with the five technology waves. While Perez has question marks for the period following publication, it is easy to imagine where to place the Great Recession of 2008 (and roughly where to contemplate the end of the current “Maturity” stage, 14-18 years later to be expected around 2026):

Another key takeaway from the Finance part of the book is how alongside each technology revolution, there is inevitably a wave of financial innovation, creating the new species of debt and equity financing needed to finance the new kinds of products and firms coming of age:

It was during the third surge that investment banking and institutionalized financial capital became a powerful and indispensable part of the industrial system. Yet, the process took some time to develop. Carnegie’s new Bessemer steel plant, the big-bang of that surge, was still funded by fellow capitalists as independent investors. Three years later, in 1878, Edison was already getting financial backing for his early projects from young Morgan’s bank. But what would become the driving power of the financial system in relation to industry was originally built upon railway stocks, government and foreign bonds, the agricultural processing business and the spread of trade, infrastructures and the exploitation of natural resources in the empire. Only when industry became heavy (with electricity, chemistry and the like) and as capital-hungry as infrastructure did financial capital really organize to fund it.

While much of the first half of the current revolution relied on traditional financing (including bring the term “IPO” into everyday conversation), it seems clear to me that “crowdfunding” is an important new form of financing that emerged from the specific circumstances of the current wave.

Near the end of the book, Perez explicitly revisits a theme that runs throughout, which is the startling similarities seen across each successive wave:

When reading the accounts of the 1870s and 1880s written by those who lived through them, one is inevitably struck by the similarities between the evolution of compound engines and ships and that of chips and computers, between the process of generation of a world economy through transcontinental transport and telegraph and the present process of globalization through telecommunications and the Internet. By making the relevant distinctions between that context and this one, the power of those technologies and of these, the worldviews of that time and our own, we can learn to distinguish the common and the unique in all such processes. The same happens when reading the glowing accounts of economic success in the 1920s and the similar writings about the ‘new economy’ in the 1990s. If one is willing to accept recurrence as a frame of reference and the uniqueness of each period as the object of study, then the power of this sort of interpretation comes forth very strongly.

Her epilogue is dated 2002, so it’s left to the reader to interpret current events against her framework. We are closing in on 50 years since the “big bang” event kicking off the Information and Telecommunications revolution, and it’s difficult not to recognize the news of the day as Perez describes some the conditions typically present in the waning days of a wave:

By the end of the installation period, polarization has usually reached morally unacceptable extremes and has probably stirred the anger of the excluded. These are the sorts of forces that can put pressure on the political world towards the necessary structural adjustments, favoring the real economy of production and restraining some of the more damaging financial practices, The outcome of such power struggles is, of course, unpredictable.

Obviously that last sentence offers little comfort in the current climate! But to take an optimistic perspective, and assume that we are also in the very early days of the next great surge, Perez’s work provides an invaluable framework for filtering events and working not to predict the future as much as sensibly plan for the likely conditions in which that future will unfold.

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital is available from the publisher.